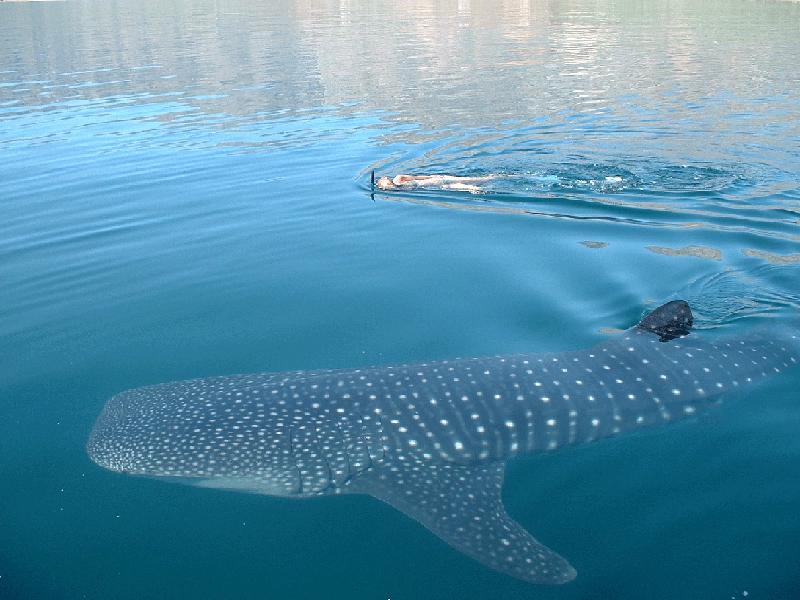

A few years ago, numbers of the mysterious whale shark were reported to be in decline. Now, thanks in part to the Internet, the mightiest fish in the ocean may be on track for a comeback.

Hunting of this harmless giant has been officially banned in most countries and trade in it is now highly restricted under threatened species treaties. But the whale shark has significance beyond its own survival – it is helping to pioneer a new technology in which thousands of “citizen scientists” around the planet play a direct role in monitoring and helping to protect endangered species.

In a breakthrough for conservation biology a technique for keeping track of endangered animals (including fish) via the internet has been developed by Australian marine scientist and Rolex Laureate Brad Norman, US computer whiz Jason Holmberg and NASA astrophysicist Zaven Arzoumanian.

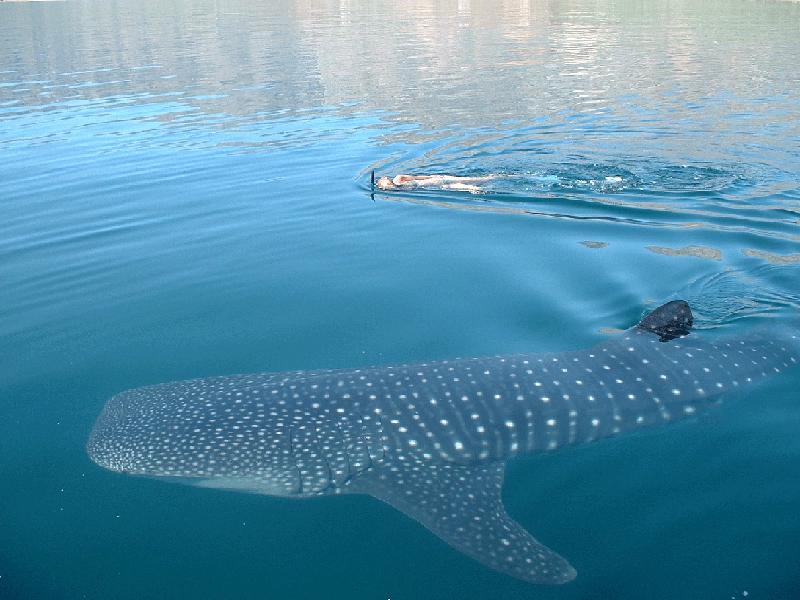

The team has adapted a mathematical formula used by Hubble space telescope scientists to recognise star patterns for identifying whale sharks from the unique constellation of white spots on their skin. Now, photographs of whale sharks logged on their website (www.whaleshark.org) by volunteer divers all over the world can be used to recognise, and monitor, individual sharks. For the first time this is giving marine scientists a feel for the numbers, global distribution and mysterious habits of the giant fish, which reaches 18-20 metres in length.

Brad Norman tested the concept at Ningaloo, off northwestern Australia. In 2006 year he received a Rolex Award for Enterprise, which is enabling him to take the technique to more than 20 countries frequented by whale sharks worldwide.

“We’ve logged 420 sharks from Ningaloo, in northwest Australia, and identified 1000 individuals worldwide since we started the library,” he says. “We’re seeing some sharks returning to WA year after year, while others are completely new additions to the ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-identification Library”.

“In the Philippines and Honduras, which were our first two spotting sites to be set up after Western Australia, we’ve logged over 100 sightings and 50 sightings respectively. Individual sharks that were seen in Honduras have also been confirmed visiting in Mexico and Belize using the Library.”

Brad says he is amazed at the enthusiasm with which divers and tourists round the world have become involved, logging over 10,000 underwater photos of 800 individual whale sharks in the ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-identification Library at www.whaleshark.org

Whale shark spotting centres are now being set up – or soon will be – in Thailand, Taiwan, the Seychelles, the Maldives, the Galapagos, Indonesia, India, the Red Sea and along the east coast of Africa – anywhere, in short, where tourists and divers gather to swim with and marvel at these remarkable creatures.

“We’re starting to get a much better picture on the whale shark’s global population and conservation status. Till now it was a pure guess,” Brad says. “Now, thanks to our volunteers with their cameras, we are gathering standardized data from all over the world”.

That data is playing an important role in helping to protect whale sharks. Since he carried out the first review of its population for the World Conservation Union (IUCN) – in which it was rated ‘vulnerable to extinction’ – Brad has campaigned internationally for greater protection. One of his most potent arguments is that a live whale shark earns a lot more from tourism than does a dead one sold as meat in the fish market. Following efforts by Brad and others, the Philippines, India and – most recently – Taiwan, have all outlawed the hunting of whale sharks. This, at least, has ended the industrial slaughter of whale sharks worldwide – though many are still killed by local fishermen.

This success is due in part to the worldwide publicity generated by the online whale shark library and its many amateur contributors. While birdwatchers have long helped provide global conservation data for migratory birds, this is the first time ever such a technique has ever been attempted for a fish. However the technology is proving so successful that, dependant on funding, the team may soon adapt it for other forms of wildlife which can be identified photographically from distinctive marks on their hide.

“We’ve had more than 30 different researchers contact us wanting to use our technique for studying all sorts of animals from manta rays to African wild dogs, from blue whales to lions and cheetahs and from wrasses to turtles,” Brad says.

“Potentially any animal which can be recognised from unique markings on its body can be identified using a simple camera, provided it is photographed in a particular way. When whale shark photos are logged in our online library each shark is assigned its own number and when someone photographs the same creature again, both photographers are informed by email. In this way you can track of the progress of ‘your’ shark as others spot it.”

In an even more dramatic advance in the study of cryptic animals, Brad Norman has joined forces with fellow 2006 Rolex Laureate Rory Wilson from the UK, who has developed arguably the world’s most sophisticated wildlife monitor – a tiny motion sensor that records the animal’s activity around the clock. Developed over 25 years, his devices can detect an animal’s speed, direction, heart rate, heat loss, feeding, diving, energy expenditure and other actions. “It’s like keeping an automatic diary of what the animal is doing and where it goes,” he says, adding it is the world’s first ‘black box flight recorder’ for wildlife. The study of energy use, in particular, can tell biologists whether an endangered animal is doing well or poorly.

At Ningaloo in June 2007 one of Rory’s monitors was for the first time successfully trialled on a whale shark, recording data about its activity and position for about an hour before breaking loose and resurfacing to be collected and analysed by the research tem. Future use of the tag will reveal much about what the shark gets up to when it is out of human camera range, the researchers hope. “It’s a beautiful alliance,” Brad says. “For the first time we have a real chance to understand the natural behaviour of this magnificent animal, even when it is deep down and out of sight.” One of his aims is to use the tag to study the impact of ecotourism on the giant fish – and whether or not its behaviour changes when in the presence of humans.

The team has also developed a stereo camera system in order to get an accurate assessment of the length of whale sharks in the wild. By comparing images of the same shark from year to year they hope to obtain a good estimate of its rate of growth.

At the same time, working with the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) of the Philippines and Denmark, Brad has been implanting whale sharks with simpler tracking devices that record their location, depth and journeys using GPS navigation. After a time the tag breaks free from the shark, rises to the surface and send back a record of its travels to the researchers via satellite.

Between the four methods – camera, activity monitor, stereo camera and tracking device – Brad is opening a window on the behaviour of one of the most cryptic beasts on the planet.

Whale sharks were first recorded in South Africa in 1828 and over the next 160 years there were only 320 confirmed sightings. The whale shark is harmless to humans, being one of only three sharks that are filter-feeders, using gill rakers to sieve krill (shrimp), small fish and other tiny sea life as its sole source of sustenance. Individuals have been tracked for 13,000 kilometres across the Pacific, and 3,000 kilometres in the Indian Ocean. It has an uncanny instinct for locating food concentrations and researchers consider that, by building up a detailed picture of whale shark numbers and movement they may gain important insights into the biological health of the oceans themselves.

“We’ve managed to raise awareness about whale sharks and to stop industrial hunting of them. The next task is to work out whether the population is declining, stable – or on the increase,” he says.

This year there was great excitement at the sighting of what may have been a pregnant female whale shark at Ningaloo, while another observer recorded what looked like two sharks positioned ‘belly to belly’. If confirmed these observations may be the first whale shark breeding behaviour ever observed.

Meanwhile sighting reports and photos continue to stream in on the internet from around the world. In the Red Sea a women diver has recruited six dive clubs to join the global whale shark spotting team and Brad is off on his travels again, with funds from the Rolex Awards for Enterprise to set up a chain of whale-shark monitoring centres round the world.

“The internet has been a key factor in the success of this project so far, by generating so many enthusiastic volunteers. Till now, most field work on wild animals has been done by scientists and their helpers. The whale shark project proves that ordinary people can play an important part in helping to conserve wildlife, and protect the oceans – by becoming ECOCEAN ‘Research Assistants’ throughout the world.”