Similan Islands and Manta Rays

One of the most amazing, and to me the most fascinating creatures we have here are the Manta Rays that call this area home. I had never seen them before and even now, after several years of diving with them – they are enthralling to see. Their movements are reserved and majestic. I still find them to be one of the most alien of our creatures.

While doing research for this I learned a lot more than I had expected. They are even more fascinating now. Read how they reproduce – wow! Similar to How eagles do, but drifting across the oceans – weightless. Ahem…

I was really amazed at how little was known about them. Something so large, so beautiful and something that we see so frequently – it was baffling how little there was about them. The first birth ever recorded only happened this year!

Below is a great FAQ written by R. Aidan Martin for the ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Because there seems to be regional variations and new information, I will include comments in italics.

Where are Manta Rays found?

Mantas are found world-wide in tropical to warm temperate seas. On the Similans they are most frequently found at Koh Bon, Koh Tachai and randomly at other sites.

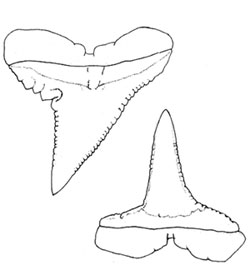

Does the Manta Ray have any teeth?

Yes, Mantas have about 300 rows of tiny, peg-like teeth, each about the size of the head of a pin. The crown of each tooth has a blunt surface with three weak ridges. These teeth are often indistinguishable from the denticles (scales) inside the mouth and are not used for feeding. They may play a role in Manta courtship and mating (see below).

How do Manta Rays reproduce?

Like sharks and other rays, Mantas are fertilized internally. Male Mantas have a pair of penis-like organs — called claspers — developed along the inner part of their pelvic fins. Each clasper has a groove through which sperm is transferred to a female Manta’s body, where fertilization takes place. During courtship, one or more male Mantas chase a female for prolonged periods. Eventually a successful male grasps the tip of one of her pectoral wings between his teeth and presses his belly against hers. Then, the male flexes one of his claspers and inserts it into her vent. Copulation lasts about 90 seconds. The fertilized eggs develop inside a mother Manta’s body for a lengthy but unknown period that may be 9 to 12 months or more. One to two pups are born per litter, but no one knows where or when Mantas give birth. There is one report from North Carolina of a baby Manta being born as its mother was in mid-leap after being harpooned, but this may not be typical. Mother Mantas may take a year off between pregnancies to re-build her energy stores.

How big is a newborn Manta Ray and where have they been found?

How big is a newborn Manta Ray and where have they been found?

Based on the smallest free-swimming members of this species, newborn Mantas are about four feet (1.2 metres) across. Very few newborn Mantas have been reported and we know almost nothing about where they are born. While there is still little known about where they prefer to give birth, there was recently a live birth at an aquarium in Japan

What is the size of the largest Manta Ray ever found?

Records of giant Mantas are notoriously difficult to verify. The largest reported in the scientific literature measured 22 feet (6.7 metres) across and there is one report of an individual 30 feet (9.1 metres) across. But most Mantas encountered by people are about 12 feet (4 metres) across.

How long do Manta Rays live?

No one knows how long Mantas live. Based on known lifespans of closely related (but much smaller) warm-water rays, Mantas may live up to 25 years or so.

Why do Manta Rays have different color patterns?

Mantas vary enormously in color pattern on the shoulders and, especially, the undersurface of the body. It is not known what functions — if any — these differences hold for Mantas, but they are very useful for researchers in distinguishing one individual from another. The shape and extent of the shoulder patches, the precise pattern of spots and blotches on the undersurface, and the lifetime pattern of scars form a pattern of markings as unique as a human fingerprint. Manta markings can be photographed and filed in an organized way to allow cataloguing all individual Mantas in a given area. There are also intriguing regional differences in Manta color patterns. For example, specimens from the eastern Pacific often feature dusky to mostly black undersurfaces, while those from the western Pacific are typically snow white underneath.

|

Cross Section of Intestine |

Have Manta Rays ever killed anyone?

There are numerous reports, mostly anecdotal, of harpooned Mantas leaping on small vessels and smashing them or their occupants. Some of these cases may have resulted in the death of one or more people due to crushing or drowning, but it must be borne in mind that the animal was simply trying to defend itself. Divers have sometimes been injured accidentally while trying to ride or photograph Mantas from too close. But there is no record of an unprovoked Manta attacking or injuring a person. A similar question – has anyone ever killed a Manta? An animal with no teeth, no defense mechanism that eats plankton.

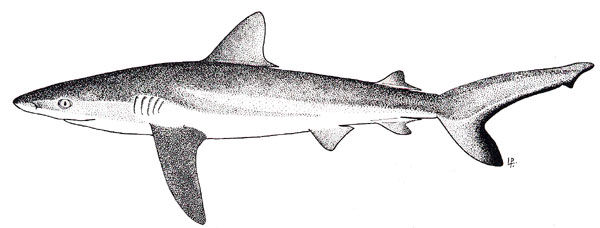

What preys on Manta Rays?

Only large warm-water sharks, such as the Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier), are known to prey upon Mantas. The head marine Biologist from the Phuket aquarium claims that they are predated upon by killer whales! Yes we do have a pod of killer whales that migrates through the area!

Is it ok to ride Manta Rays?

No wild animal is benefited by being ridden., and Mantas are no exception. Riding a Manta increases its swimming effort — using up calories that might have been better used growing, reproducing, escaping predators, or healing wounds — and may stress the animal unduly. While riding Mantas, people have scraped their skin, gone too deep, risen too fast, or fallen off and been injured accidentally. Simply touching a Manta may remove some of the mucus coating that protects the animal from marine infections. Last, but not least, some Mantas clearly do not like being touched and may speed away, ending the encounter by sheer distance. For all these reasons, touching or riding Mantas is to be avoided. We also see it as extremely vain to think that one of the most majestic animals on earth should be ridden. Not only is it a clear and public display of ones ignorance, but should be reported to marine park rangers. The operator that allows this activity should also be reported, and as things don’t always get accomplished through the courts, please post the name and details of the operator on forums like lonely planet and scuba forum.

We feel VERY STRONGLY that interference of any kind with the marine environment is shameful and to be avoided.

Why are Manta Rays bodies flattened?

Mantas bodies are flattened from top-to-bottom because their ancestors were, too. Mantas are derived from stingrays, which are flattened bottom-dwellers that swim by undulating their expanded pectoral fins. This flattened body form is advantageous for hiding in the bottom sediment, making it difficult for predators to see partially buried stingrays. During the course of their evolution, Mantas lost the stinging barb and their pectoral fins developed into graceful, flapping wings, but their flattened body shape remained.

Do Manta Rays migrate?

Given the scattered nature of their planktonic food, it is very likely that Mantas migrate. But little is known about where they travel and when. Each autumn (March-April) at Ningaloo Reef, of the coast of Western Australia, Mantas appear in large numbers, apparently to take advantage of the rich feeding afforded by the mass spawning or corals and other reef creatures that takes place at this time. Where the Mantas go when they leave Ningaloo is not known. Manta movement patterns are presently being studied by tagging and sonic telemetry at numerous locations, including Ningaloo Reef, the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, Hawaii, and the Sea of Cortez.

Do Manta Rays sleep?

No one knows. In vertebrates (backboned animals), sleep is characterized by a profound change in brainwaves. This has never been demonstrated experimentally in Mantas or any other elasmobranch (shark or ray). Actively swimming sharks and rays, such as the Manta, are believed to swim constantly, never stopping from birth to death. Although it is feasible that some parts of the brain shut-down while the parts of the brain responsible for coordinating swimming movements stays awake, this has not been demonstrated experimentally.

Are Manta Rays social?

Are Manta Rays social?

Apart from courtship and mating (which is quite elaborate, see above), Mantas do not appear to be particularly social. Mantas frequently aggregate at rich feeding sites and cleaning stations, but there is little evidence of social interaction among them. Actively predaceous animals — such as lions, wolves, sharks, and dolphins — often establish social hierarchies (structures) and signals. Outside breeding season, most passively grazing animals — such as cows, deer, antelopes, and apparently Mantas — show little awareness in one another other than avoiding collisions.

Are Manta Rays more active by day or by night?

Mantas are most commonly seen during daylight hours because that’s when most observers are most active. We have virtually no idea what Mantas do at night or how active they are. Manta courtship (see above) seems to feature prolonged chasing, which would be best accomplished in clear, open water during the day. Mantas may feed most actively at night, when many planktonic creatures rise surfaceward, providing a rich bounty on which Mantas may feed. Beginning about an hour after dark at a certain seaside hotel on the Kona Coast of Hawaii, groups of Mantas are often observed feeding on krill and other planktonic organisms concentrated in the hotel’s underwater lights. Unfortunately, this spectacle has largely ceased, possibly due to too much interaction from the throngs of excited divers and snorkellers who converged on the feeding Mantas.

How deep do Manta Rays swim?

Divers have observed Mantas as deep as 100 feet (30 metres), but no one knows how deep they can swim.

What is the difference between mantas and mobulas?

Mantas and mobulas (also known as “devil rays”, of which there are 9 species) are similar in form, sharing paddle-shaped cephalic lobes and gracefully curved pectoral wings. Mantas grow much larger than mobulas. Mantas reach widths of at least 22 feet (6.7 metres), while most mobulas are 3 to 10 feet (1 to 3 metres) across. Mantas and mobulas are most readily distinguished by the position of the mouth: in Mantas, the mouth is terminal (located at the front of the head), while in mobulas the mouth is subterminal (located underneath the head, as in many sharks).

What are cephalic lobes and what is their function?

The forward-pointing, paddle-like organs at each corner of a Manta’s mouth are termed “cephalic lobes”. They are basically forward extensions of the pectoral wings, complete with supporting radial cartilages. Mantas have been observed using their cephalic lobes like scoops to help push plankton-bearing water into their mouths. When Mantas are not actively feeding, the cephalic lobes are often furled like a flag ready for storage or held with their tips touching like the swinging doors of an Old West saloon. Either of these cephalic lobe positions may reduce drag during long-distance swimming.

Why do Manta Rays sometimes jump out of the water?

Mantas may leap completely out of the water for a variety of reasons. They may do it to escape a potential predator or to rid themselves of skin parasites. Or they may leap to communicate to others of their own species — the great, crashing splash of their re-entries can often be heard from miles (kilometres) away. It’s anyone’s guess what they may be trying to communicate. Leaping male Mantas may be demonstrating their fitness as part of a courtship display. Since these leaps are highly energetic and often repeated several times in succession, they may simply represent a form of play.

Have Manta Rays ever been exhibited in an aquarium?

Very few aquariums have the enormous tanks and filtering capacity needed to display a full-grown Manta. Although there have been many valiant attempts to display Mantas in aquaria, most specimens refuse to feed and die within a few hours or days of being deposited in a tank. The Expo Aquarium, in Okinawa, Japan, has successfully maintained Mantas for as long as 36 days. Despite the failures of the past, several large aquaria continue to refine and test capture and transport methods toward the goal of maintaining a healthy Manta in captivity indefinitely. It seems that this is no longer true. Again, the trapping and caging of such creatures is a real shame.

Are Manta Rays hunted anywhere in the world?

Are Manta Rays hunted anywhere in the world?

In the 1990’s, targeted harpoon fisheries in the Philippines and off the Pacific coast of Mexico decimated resident populations. Due to the scarcity of catches, Mantas are rarely targeted in these locations today. Mantas are sometimes ensnared in drift or set nets, particularly in tropical parts of the western Pacific and Indian oceans. These catches are rarely reported, so it is difficult to assess the threat posed to manta populations by these “incidental” captures.

Do Manta Rays have any monetary value?

Mantas are valued commercially for their tasty meat, sandpapery hide, and oil-rich liver. A Manta in captivity is worth a small fortune to any public aquarium with the facilities to display it, a reality that drives a small but recurrent harvest in Japan and possibly other areas. The monetary value to the diving and snorkeling industry is enormous. By observing one manta, we will generate thousands of Euros into the local economy. Additionally this will be recurring income, rather than a one time catch. Please don’t purchase any products from Mantas or other species while in Thailand.

Are Manta Rays in danger of extinction?

We don’t know. Mantas seem to be fairly abundant in some areas, rare or absent in others. Until we understand the extent and dynamics of Manta stocks, there is no way to assess their conservation status. Based on their low birth rate, Mantas are probably highly vulnerable to sustained fishing pressure and habitat degradation. This likelihood would seem to favor a cautionary approach to Manta exploitation and management until such time as we have the sound scientific data to make a more informed assessment of this species’ risk of extinction.

Why are Manta Rays important?

So little is known about the basic biology and life history of Mantas, little can be said about their importance from a scientific or ecological standpoint. It can be argued that Mantas are important because they add to the beauty, diversity, and mystery of our world. Without Mantas, our planet would seem a significantly poorer place.

Mantas are most frequently seen in February and March with plenty of sightings outside that time. We offer daytrips and liveaboards that offer great chances of seeing them.